By Francisco Chiquete

Outside, the gusts of wind howled ferociously. Inside, the wooden walls of the house shook harder each time. My brother and I had naïvely stayed behind to guard the house, not really knowing what it was we were protecting. Then, the beam cracked, and when we looked up, the tar-covered sheets were already gone.

“Let’s go!” We ran out through the back door—the same one my mother had used to flee with her eight daughters, while my father carried the radio, the only appliance we owned. Fifteen meters away, among wash basins and narrow alleys, stood Mario’s house—newly built, solid, and spacious—which he had generously opened to neighbors as a refuge.

It wasn’t hard to find which room my family was in. We were guided by my father’s loud snoring—oblivious to Olivia’s fury, he had stretched out on a whitewashed plank left by the masons and slept soundly. The children kept peeking curiously toward that thunderous sound.

The sturdy shelter gave us courage, but every time the wind gusts strengthened, the women’s prayers grew louder, and they jumped in fright when branches—torn from near or distant trees—crashed against the windows.

The men tried to calculate how long the storm would last. “Two hours,” said one optimist. “All night,” another predicted. Olivia shattered all popular wisdom. At the start of the storm, my mother sighed in relief at the sound of thunder. “Cyclones don’t bring thunder or lightning,” she said.

But this storm, which struck on the night of October 24, 1975, brought everything. Strangely, the wind came before the rain—and didn’t let up. For nearly two hours it battered the houses and the trees; it felt like it was pounding the whole world. When the rain arrived, it lashed with a violence none of us had ever experienced. The drops were like stones hurled at the walls, doors, and windows.

Suddenly, silence. No rain, no wind. The adults cautiously began stepping outside to assess the damage. Some mothers lifted their children, ready to return home—but one person warned against it: “Who knows how the houses ended up? And without light, you can’t see the dangers.”

Waiting for dawn, they spent the time talking, smoking, recalling past hurricanes. We thought we had survived, and that was what mattered—but it wasn’t over. Soon, the rain began again, and the winds returned, thrashing the treetops. Within minutes, the intangible monster was upon us once more.

Doors and windows were barricaded again. The gusts of wind and sheets of rain were merciless. “The bastard came back!” someone shouted. It couldn’t be. Hurricanes don’t turn around. “It must have hit the mountains and bounced back,” someone theorized—and that same idea spread among the people of Mazatlán. None of us knew that the calm we had taken for the end of the storm was actually the eye of the hurricane—the still center around which wind and water rage. Perhaps no other had passed so directly over Mazatlán, or been so vast that we could perceive the eye’s dimensions.

Two hours later, real calm returned. The streets looked bleak, not a single light near or far. This time it was truly over—the wind and rain, at least. But the consequences remained. The muddy waters of the Jabalines stream overflowed across the Estero del Infiernillo and jammed up under the Juárez Bridge, where high tide blocked their exit. Flooding spread through the neighborhood and all others along the stream and the storm drains, like the López Mateos colony.

With no electricity, few businesses could operate. Buses were idle because gasoline and diesel were scarce. Gas stations could only pump manually, taking twenty to thirty minutes to fill half a tank. The lines were endless.

We had never endured a stronger hurricane—winds of 180 km/h and gusts up to 230. It was madness. We never imagined we’d live through something so intense.

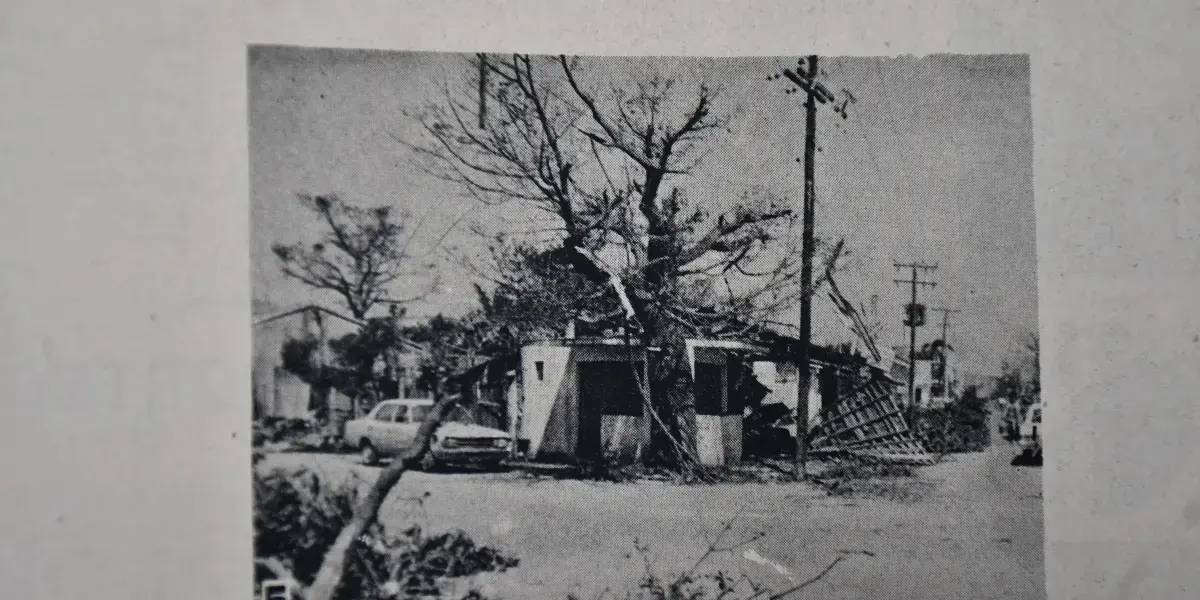

Then came the news: eight dead… twelve… sixteen. Some said twenty-four, though it may not have reached that number. Over a week without running water or electricity—but most astonishing were the shrimp boats stranded in the streets of Urías, several blocks from the estuary, where they had been taken for shelter.

The train that had stopped to avoid danger derailed anyway. The wind knocked it off balance; the cars lay half-tipped over. Inside one or two of them they found bodies—likely homeless people or neighbors who had sought refuge within the iron walls.

With store shelves empty, anyone who found flour to make tortillas—or beans for a meal—was lucky. Corn flour vanished, and only black beans remained, long disdained by locals who preferred the yellow variety. Even back then, panic buying was a tradition whenever a cyclone warning was issued.

El Sol del Pacífico printed its editions in Culiacán. El Correo de la Tarde reverted to old-school technology. Lencho and Venancio, master typographers, set each line letter by letter, while Jorge “El Chato” Osuna assembled the pages—called “ramas”—secured them, and, with everyone’s help, turned the great wheel of the flat press to make the drums and paper roll. Don Octavio Lango was persuaded to use his ancient chemical formulas—mixtures of egg, vinegar, and grease—to transfer photo images onto sensitized plates. It was an anachronistic feat. That afternoon, “El Barbitas,” also known as El Gritón, and Lao, the blind news vendor, went out shouting the headlines through the streets.

Recovery took months of effort. Some businesses never reopened, and many residents began searching for safer places to build their homes—but the flood-prone neighborhoods remained where they were. There’s always someone in need willing to live in danger.

In fifty years, no other hurricane of that magnitude has struck Mazatlán—but today’s storms are stronger and more dangerous. On September 29, 1976, Hurricane Liza was heading straight for Mazatlán. A vault of black clouds had taken over the sky, and the pressure warned of disaster. Authorities braced for another blow. Suddenly and unexpectedly, Liza changed course—and on October 1, it struck La Paz, the capital of Baja California Sur, killing 416 people and leaving 20,000 homeless. Liza then crossed the Gulf of California and hit Los Mochis.

Comments (0)